This is the second installment in a series of posts about our scooter trip around West Africa. If you need to catch up: Part 1.

The above picture sums up my time in Dakar. Along with several associates, I was more or less a complete degenerate. The oversized blanket I was parading around with was given to me by a waitress who recognized that I was freezing cold and possibly mentally ill. This is what happens when you ride 1,200 km in 3 days on a Chinese scooter and then have a booze-fueled reunion with friends.

Dakar was too much fun. C’était la fête quoi. Let’s flash forward to where I can remember things clearly: our departure. I was sweating alcohol and battling a nauseating headache, but I managed to stay upright on the jakarta and make it to the highway. The omni-directional wind situation had not changed. Except now we were dealing with what my friend Hannah would call an existential hangover. If we got anywhere close to the Gambian border, this day would be considered a massive success.

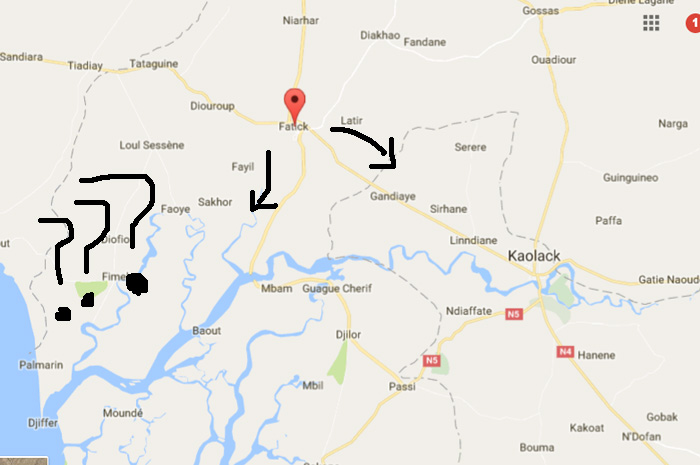

At Mbour, we took a slight detour to the beach resort town of Saly. It was a bit too much of a beach resort town. We grabbed a quick lunch and then continued towards Fatick. Before we arrived there, Matt made a smart call to pull off the road near a large tree. It was time for a nap.

Almost immediately after hopping off my bike, I stepped on this:

Things were not going well at this point, but 40 minutes of deep sleep can change everything. Fanned by a light breeze, we laid out our bedrolls and passed out. This was the first step in a miraculous recovery.

I still felt as if I had been struck by a blunt object when I woke up, but my energy had returned. We got back on the bikes with renewed purpose. Further down the road, we stopped in a village where I got a haircut by Lamine, an entrepreneurial young man who was selling clothes and renting speakers for ceremonies in the same space as his barbershop.

Lamine in his place of business.

After a 50 cent haircut and some good conversation about life in rural Senegal, we were back on the road. Before long, we were in Fatick, a charming town surrounded by salt marshes. Fatick’s historical importance is tied to the Serer ethnic group, the third largest in Senegal. Many of Senegal’s most well known cultural innovations have their roots in the Serer Kingdom of Sine, including the Sabar drum. We took our time rolling through the town, and then we had a decision to make.

We could head directly south on an unfamiliar road towards a river crossing, of which we knew nothing, and then bush camp somewhere. Or we could go to the larger town of Kaolack and find a hotel. The first option was a big question mark, so we chose that one. It turned out to be the right decision.

It was a gorgeous ride down what’s apparently called the R61. The landscape alternated between salt marshes and patches of forest. We crossed narrow causeways over shallow water where egrets waded. Every now and then a sept place cruised past, but we mostly shared the road with donkey carts and groups of high-school-age kids taking their time on the walk home.

It’s always enjoyable to see a goat free-styling on a donkey cart (or a horse cart in this case).

The road ended abruptly at a river crossing. There was a ferry making its way over from the other side, but the sun was setting and we still didn’t know where we were going to sleep, so we opted for one of the private pirogues that was already filling up with passengers. The jakartas were hoisted up and we squeezed in as the last two on board. Everyone was given life jackets and off we went.

On the other side we found ourselves in Foundiougne. Families sprawled out on thatch mats in front of their houses, joking and playing cards as the sun went down. We stopped at a boutique run by two friendly Mauritanians and bought water, canned mixed vegetables and a few onions to supplement our instant noodles.

We headed out of town to scout for a place to camp. We came up empty for a few kilometers, but then found a stretch of beach perpendicular to one of the causeways. Cutting back in from the beach, Matt spotted what turned out to be the perfect bush camp, flat and open in the middle but surrounded by trees.

We set up camp and then cooked our deluxe instant noodles, with the extra ingredients we bought chez les Mauritaniens. Sleep came easy, but I was quickly woken up by what sounded like a roaming pack of wild dogs. They were not in our camp and were probably somewhat far away. I was shitting bricks nonetheless. Matt was unconcerned, and with good reason. We were not far from several villages. The threat from wildlife was minimal. If we were going to have an unlucky interaction with an animal, it was going to be a goat wandering into our camp and eating our oreos. I went back to sleep and woke up at sunrise.

Feeling refreshed, we packed up our camp and got ready for a relatively light day of riding. We did have a border crossing in front of us, though, and another water crossing. The road was quiet until we approached Karang, on the Gambian border. We checked out of Senegal in a few minutes and then heard our first “Welcome to the Gambia.” It’s always bizarre when you can walk 50m and everything switches from one language to another. Of course, everyone on both sides was speaking Wollof.

I had another chance to try my Malian identity card, and this time I was successful. I paid $2 for my laissez passer instead of the $25 visa on arrival I would have been obligated to purchase otherwise. I am Malian after all!! The customs agents made their play to get an extra $10 off us, but nobody took issue with the actual paperwork of the jakartas.

From the border, it was a short ride to Bara and the day’s main event, the ferry to Banjul. The ferry has set departure times and we happened to arrive when it was leaving. We quickly bought tickets and gunned it down the pier, cheered on by the dockworkers gesturing wildly for us to hurry up. We made it on, but the ass end of my jakarta was hanging off the edge of the boat and they couldn’t secure the gate. After some careful arrangements, we somehow fit both jakartas in between a minibus and a very unhappy cow that was tied up and laying on the ground.

The ferry crossing takes about twenty minutes. It was a pleasant ride. I ate orange slices and scanned the horizon for interesting river boats while trying not to trip over sacks of rice.

We were the last ones off the boat. After skating around a few trucks, we made it out of the port, avoiding the chaos that was accumulating around the vehicles that had already disembarked. We ended up next to the Gambian river on an empty strip of road that did not look right. Clearly this was not the road we were supposed to be taking?

We timidly pulled up to a police checkpoint to ask some questions. Yahya Jammeh, Gambia’s ruler from 1994 until just a few days before we arrived in the country, had just left for permanent exile in Equatorial Guinea. This was good news for the country and the region. That said, the new president Adama Barrow had not yet been inaugurated (he would arrive several days after us), and we had little information as to how police were conducting their duties in this period of limbo.

But the police were all smiles and happily told us that we were on the right road to the Senegambia junction, where Matt needed to drop off his passport to get a Guinean visa. It was late afternoon, but still within the limits of restrictive embassy hours. We made a beeline to the Guinean embassy only to find out that the consular officer had gone out. The security guard told us to come back later. We went off to get water and sim cards. When we returned, the security guard spelled out that this dude was not coming back anytime soon. “You must return in the morning.”

The consular officer was sounding increasingly elusive, so we decided to find a hotel nearby in order to stake out the Guinean embassy the following day. It was immediately clear that Serekunda, a kind of suburb of Banjul, was a parallel universe of the United Kingdom. This was part of the menu at our hotel:

Premier league football was on every TV screen at the bar and a full English breakfast was available at any time of day. It was surreal, but then again, Gambia continued to be part of the Commonwealth long after independence. Jammeh severed ties in 2013, but Adama Barrow has already talked about rejoining the union. Serekunda seems to exist in its own particular British bubble. Many British expats have taken up residence in the suburb, and Thomas Cook has a seasonal colony of holidaymakers around the corner.

The Dandimayo Hotel was excellent, though. Great staff, good food, cold beers and well-appointed rooms.

Down the street from the Guinean embassy, we found a car/moto wash. The jakartas were a bit dirty after 1,400 kilometers.

We had two things on the docket in Serekunda. Matt needed a Guinean visa, and I wanted to meet up with Simon Fenton, who I have corresponded with online for the past several years. Simon owns an ecolodge in Casamance that he runs with his wife, Khady. He is also an author, having now written two books about his newfound life in West Africa. Matt and I planned on staying at his place in Casamance, but we would also cross paths in Serekunda as Simon was working on the Bradt guidebook for the Gambia.

After a few Julbrews

We met up with Simon at one of the many bars on the Senegambia strip and quickly discovered we enjoyed each other’s company. We downed Julbrews at a good clip as we exchanged stories and extracted all the Guinea-Bissau and Guinea-Conakry knowledge from Simon’s brain.

Later in the evening, Simon took us to a Liberian bar where the beers were almost free. The kitchen behind the bar churned out fried chicken and collard greens and the stereo cranked Nigerian pop songs. After the Liberian bar, we made our final migration to an open air nightclub. It was good fun, but things started getting hazy and I was running out of steam. The last thing I can remember was twisting the dj’s arm to play Sidiki Diabate. I promptly collapsed when I got back to the hotel.

I had a manageable hangover the following morning, nothing like the aftermath of Dakar. Before the julbrews had taken hold the previous day, we had talked to Simon about taking the scenic route to Casamance. Instead of the Senegambia highway, we would take a quiet road on the Atlantic coast and cross into Casamance on a canoe.

It took us less than an hour on a sealed road to get to the border. It was another beautiful ride. Since heading south from Dakar, the scenery was increasingly dramatic, and we were really looking forward to what lied ahead in Casamance.

We pulled up to the Halahine River, where there was a very relaxed Gambian immigration officer stamping passports. We checked out of the Gambia and then went looking for the pirogue that would take us across the river into Casamance. Once we found our man, we explained that we had the jakartas to transport as well. His non-reaction made it clear that this would not be the first time his pirogue was loaded with motorcycles. We pulled up to the river and unloaded our baggage. Ganja smoke wafted out of the small bar at the water’s edge. We chatted with a friendly Gambian girl and a rasta as the bikes were loaded onto the boat.

Loading up the jakartas

A shot of the river taken by Oumou the Drone (named after Oumou the Rabbit who outlived all the other rabbits at the Sleeping Camel. We are hoping Oumou the Drone has similar longevity). South of the River is Casamance, Senegal, north of it is the Gambia.

There is no immigration post on the Casamance side of the river, so we technically reentered Senegal as undocumented aliens. A problem for another day. We hopped on the bikes and headed down a sand track straddled by dense forest. Abené was just a few kilometers away, but the skinny tires of the jakarta struggled in the sand. While we did nearly fall off the bikes at every turn, we actually had a ball fish-tailing through the jungle, and it was one of the most memorable rides of the trip.

Eventually the jungle thinned out and houses started springing up. We were soon on the main drag of the village of Abené. Our eyes grew wide at the sight of small buvettes and maquis. This was our kind of town.

Simon’s place is called The Little Baobab, but most Abené residents know it as Chez Simon and Khady. It didn’t take long to find someone that knew where it was located. He was even willing to show us the way on his bicycle.

Simon was still in the Gambia, but we were warmly greeted by his family. Khady showed us to our bungalows, which were built with materials readily found on the property. They were clean and comfortable, a lot more so than we expected for a jungle lodge.

A part of the Little Baobab as seen by Oumou the Drone

I don’t want to get carried away with the superlatives, but the Little Baobab is a special place. At no point did I feel like a paying customer at a hotel. I felt like a member of Simon and Khady’s family. The teranga (Wollof for hospitality) was in full effect.

The other guest that was staying at the Little Baobab while we were there, Rusty aka Daddy Cool, was one of many repeat visitors to the hotel. In fact, his daughter was also a repeat visitor. It was easy to understand why. In addition to the hospitality, the place is just relaxed. You can feel your blood pressure drop when you walk through the gate. The icing on the cake is Khady’s excellent cooking and a bar stocked with ice cold Flag and Gazelle.

poulet braisé, one of the many delicious meals we ate at the Little Baobab

Simon and Khady’s place was an attraction in itself, but the village of Abené had plenty to boast about as well. Once we settled into the Little Baobab, we had a wander around town. After twenty minutes of enjoyable meandering, chatting up roadside vendors and scouting small bars and cafés, we arrived at the beach…

…where we found cold gazelles. There were maybe 6 or 7 other people on the beach. Two girls joined us in the bar and we had a funny conversation about our jakarta trip and Yahya Jammeh. We headed back down the main drag while there was still daylight. Multiple reggae parties were on offer that evening, but we retired early to the Little Baobab where we enjoyed a few beers and the poulet braisé pictured above.

The following day, we made a trip up to the Gambian border to get our paperwork in order. The Senegalese immigration officer was not impressed with our cross-the-border-on-a-canoe maneuver, but a cold drink helped change his demeanor. Afterwards, we visited the larger town of Kafountine, also on the coast.

An arrogant pelican walking around an auto repair shop in Kafountine

In Kafountine, we stopped at a small bar and restaurant called Chez Khathy. I ate monkfish brochettes and drank an icy Gazelle. The fish was exceptional, tender but firm, perfectly grilled with a citron marinade. It was one of the most memorable meals of the trip and my life. It cost about $5 in total.

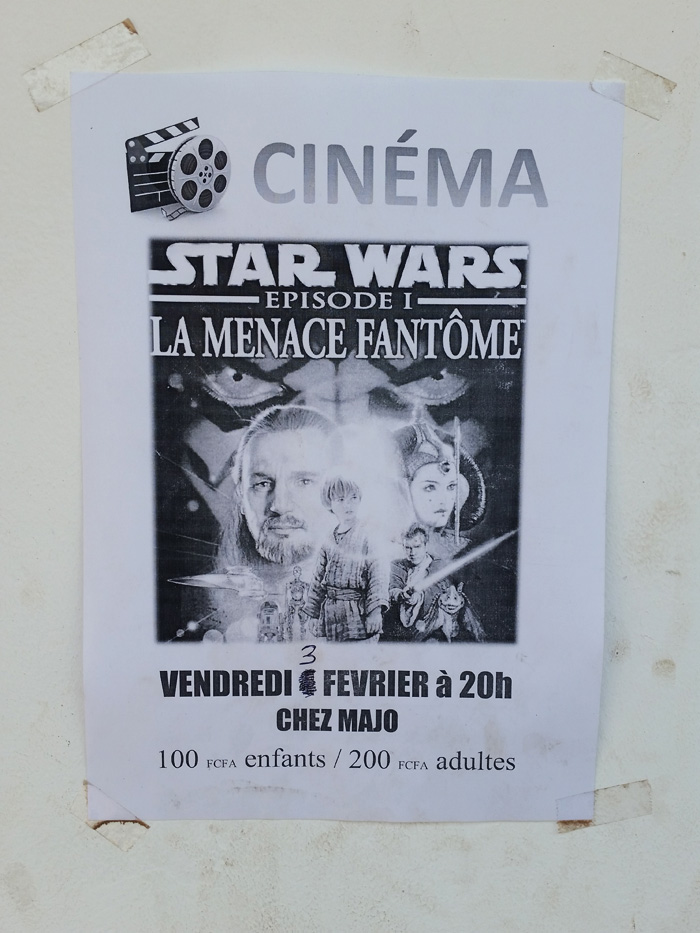

Unfortunately, we were a few weeks late for the screening of the Phantom Menace, a real bargain at 40 cents.

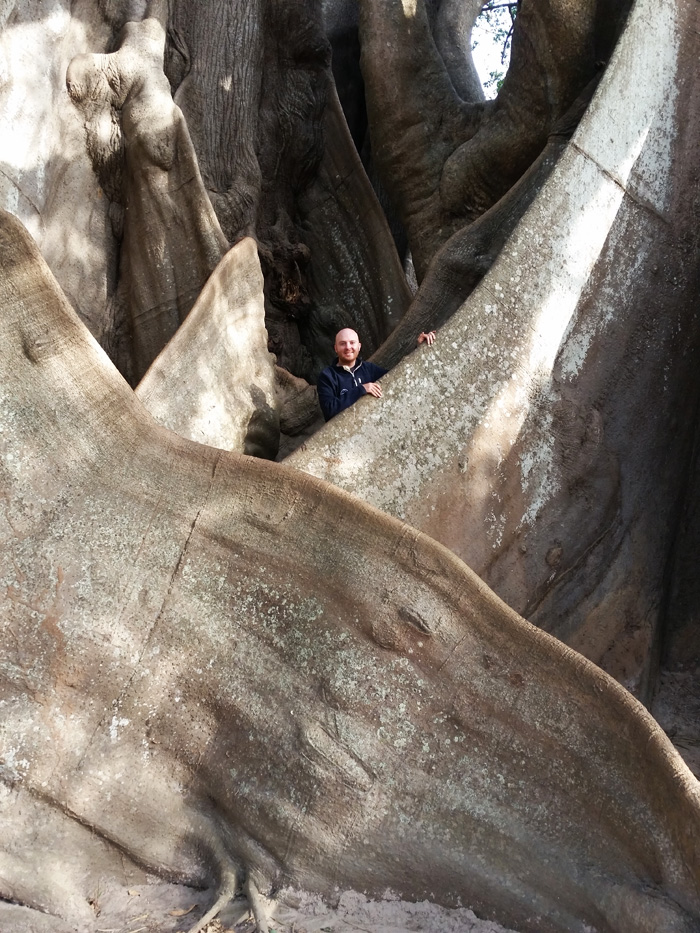

Back in Abené, we visited the sacred Bantam Wora, 6 massive fromager trees that have joined together into a true freak of nature:

The sacred tree(s) of Bantam Wora and Oumou the Drone almost getting KO’ed by a yellow-billed kite.

To get a sense for how big the tree truly is, have a look at the following picture of me inside the tree’s roots.

Holy crap

Bonfire at the Little Baobab with Simon and Khady’s family and Daddy Cool

Working on my tan with a little help from the red earth

Rice with a sauce from Casamance called kaldou. Chili, lime and hibiscus leaves drove the flavor. Another delicious meal in Abené.

Back on the beach. Stay tuned for the feature film

We were reluctant to leave Abené and the Little Baobab, but Bissau was calling, and so were Bintou and Andre back in Bamako. We said farewell to Khady and the family and Daddy Cool. It was time to head to Ziguinchor, the capital of Casamance.

Up next: The majestic roads of Casamance, riverside beers in Ziguinchor, and our first Lusophone country. Bem vindo a Bissau!!! Click here for the next chapter.

Stunning arial shots Phil – I think I need a drone! I’m really enjoying following the journey and so glad you enjoyed your time at our place. Can’t wait to catch up in Bamako.

Looking forward to it 🙂

Hey Phil,

that’s really nice writing. I could feel the African sun on my shoulders as you bumped your way along the road. Great story. As always your writing and stories make me miss Africa so much. I want to smell it again. Judy

Have really enjoyed reading this. I visit The Gambia quite regularly so recognise the feel of a lot of this even though I’ve barely touched on Senegal. On my most recent visit, I also took a drone which works fine in the UK, but could barely take off in The Gambia without losing signal and returning to base. I don’t know if you’ve had anything similar- I’ve not been able to find anything about problems like this online.

Hi Steve,

I had some issues myself and I think it may have something to do with the amount of dust in the area during that time. The harmattan period brings dust from the Sahara and spreads it all around West Africa, including the coastal areas. If it wasn’t that, I don’t know what the cause is. Interesting we both had the same issue.

Cheers,

Phil