Four hours into a 35 hour bus ride and the sky dropped an ocean on western Mali. Rivulets formed in an instant and brown water submerged a police checkpoint, normally a hub of commerce but temporarily abandoned because of the storm. My seatmate moved to the stairwell, a seat I am familiar with, when the pop-up vent above us broke, creating a small waterfall. I was already soaked through from a crack in the window. My backpack and everything inside of it was saturated.

When the driver began to overtake another vehicle, the lake of water inside the bus became deeper on the right side. When he completed the pass, the tide went out and flooded the left side. Twice, my flip flops washed away, into the aisle, where an enterprising five-year-old was collecting debris.

Then the driver pulled over. I have never seen a driver in West Africa defeated by weather. A blown tire, yes. Empty gas tank, axel giving out, upside down truck in the road, yes, yes, yes. Rain? Never. But this was more than rain. This was a torrent, a truly punishing amount of water. Le chef du voyage smartly recognized that our bus was not amphibious.

On the side of the road, the bus shook as the winds approximated a cyclone.

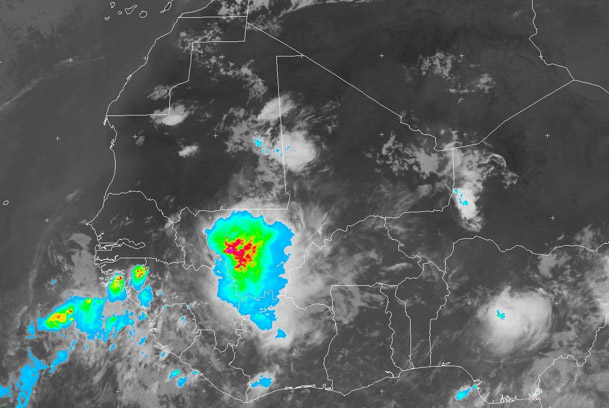

It’s hard to overstate the power of Sahelian thunderstorms. The coastal countries of West Africa have persistent rains but few actual storms. Inland, the Sahel hosts a yearly collision between moisture from the south and hot, dry air from the Sahara. This is where the seeds of Atlantic hurricanes are planted. It’s no coincidence that hurricane Katrina happened in 2005, West Africa’s most violent rainy season in the last 30 years.

This is not the storm that was rattling my bus, but it might as well have been. The picture was tweeted to me on June 20th by Captain Yaw, a pilot in Ghana who is involved with the incredible Medicine on the Move project. (I will not go on a tangent here. You can see my 7 links post for more on why I love twitter.)

800 km tall.

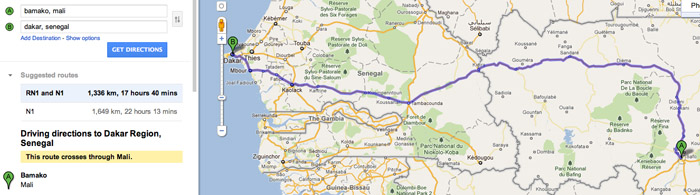

Every transport agency running buses between Dakar and Bamako will tell you that the journey takes 24 hours. It doesn’t, though. My friend Sunny and I spent 40 hours on the Dakar to Bamako bus. Her return trip to Dakar was 48 hours. This trip would take me 35 hours. After chatting up some of the other passengers, I learned that none of them had made it in less than 30.

For this trip to Dakar, I took Gana Transport, a Malian company that was widely recommended. In Bambara, Gana means okra sauce (ga=okra, na=sauce). It could also mean something else. Bambara is a tonal language. “Ba” means goat, mother, or river, depending on how you say it.

The weather was inconvenient, but it only delayed us a half hour or so. Excepting a relatively short stretch around Kayes, the road between Bamako and Dakar is in good shape, and our bus, while well worn, was not sluggish. According to Google maps, the journey takes about 18 hours.

How does 18, or 24 hours, become 30, 35, 40, 48?

It is the police and customs checkpoints (les douanes) that pile on the hours. At one checkpoint in eastern Senegal, two customs officers pulled off all the bags on the bus. Every single bag. It was 4AM.

Presumably, customs agents are looking for some form of contraband, or merchandise upon which a duty can be levied, but most people would say that what they are really searching for is a secondary income. I don’t know how much customs agents are paid. I don’t know how much revenue Senegal (or any country in West Africa) makes from their internal checkpoints. I do know that these customs agents regularly extort money from truck drivers, bus passengers and other travelers.

This system is broken. Between the delays and financial cost, these checkpoints present the greatest barrier to trade in West Africa. For more on this, check out Borderless.

We spent two hours at the checkpoint. The customs agents meticulously went through every piece of luggage. One trader had to pay money for her sacks of rice. In an hour, we would repeat the same process further up the road.

Four hours earlier, we were at Senegal’s doorstep. Nineteen hours before that, we began our journey in Bamako.

The border offered its own kind of delay. It was midnight. Everyone was tired and settling into that mode where fatigue overrides discomfort. My contorted legs gave up their struggle, my muscles caved, my eyes closed. Then the bus stopped and everyone had to get off.

After carrying my body through the immigration proceedings, I sat down on a wobbly bench with Ibrahim, my seatmate on the bus. While most of the other passengers were revitalized by the night air, I was half-conscious with heavy limbs, perhaps because of my strategic decision to eat and drink as little as possible during the voyage. Or perhaps because we had been traveling on a hot bus for 19 hours. Either way, I ordered some brochettes and broke my fast.

Ibrahim was making this journey for the first time. He was already dismayed by the length of it. We talked in Bambara and French and quickly discovered we were joking cousins. My Malian family is Dogon, his was Sonrai. He called me an onion farmer and said I was his slave. I called him a bean eater and said I was his father. The brosetitigi (literally “owner of the brochettes,” but here meaning “brochette seller”) got involved and told us that we were both, in fact, her slaves. She explained that her last name was Keita and she was a descendant of the first emperor of Mali, Sundiata Keita. We both laughed, Ibrahim doing so with some dramatic finger wagging. Then it was time to get back on the bus.

The border crossing at Kidira involves an off road detour. I would like to think that this is because the tarmac is under construction/renovation, but I don’t know for sure. On the way to Bamako two months earlier, our bus struggled through the sandy track, bottoming out and stalling, but it never broke down.

This time, our driver, perhaps spooked by the bus in front of us, which was impossibly lodged in one of the track’s larger craters, ordered everyone to get off the bus. Most of the passengers, including me, were confused. Ibrahim asked “goudron bε min?” (where is the paved road?).

Free of passengers, the bus sped off. It teetered like a boat in the distance and then disappeared. After twenty minutes of stumbling through puddles I was back on the bus. Families and elderly passengers took longer.

The idling bus had become a haven for mosquitos. I could not go back to sleep. I commissioned a bounty hunter, offering Mamadou, the five-year-old who previously collected my flip flops, 25 CFA (about 5 cents) for every mosquito corpse he brought me, but he fell asleep before killing any of them.

The last thing I wanted to do at this point was grapple with my departure from Mali, but that’s where my mind was headed. I put some doussou bagayoko on the headphones and became deeply sad. My malaise persisted through the night. When the sun rose, I found sleep. We arrived in the early evening.

The sandy streets of sacre coeur III, the infinite breeze of dakar, and the lilting rhythm of tama ji broke my sadness. The sun went down and the generators turned on. I washed off the dirt in a dark shower before going to bed in an empty dormitory.

……

For some truly beautiful and transporting writing (and media) about changes in the Sahel and what it means to travel there, specifically Mali, please read this post from Chris at Sahel Sounds. I had the pleasure of meeting Chris in Bamako a few months ago. I don’t know of a more engaged explorer of culture in this part of the world. Seriously, his site and his business, signing underrepresented musicians and producing and distributing their music, are something special. And this post is a real work of art, complete with words, photos and sounds. Check it out.

One last thing, if you have a minute to spread the word about this post on howtodrawcamels.com, I would greatly appreciate it. I’m trying to raise the profile of Mali Health Organizing Project, a highly effective social enterprise in Mali that is doing some very meaningful work. They are running a summer matching campaign and if you have a few dollars to spare, I can guarantee they will make an impact. Regardless, you can always spread the word about them. It takes about 5 seconds.

Hey Phil, I recently found your blog and have had trouble tearing myself away from your archives. I love reading about your experiences and thoughts, and you describe things really beautifully (like in this post!). I’m originally from South Africa (been in the U.S.) for several years, but would love to travel to other parts of Africa so it’s great to hear your tales. I’ll be sure to spread the word about the Mali Health Organizing Project.

Jaclyn,

Hi. Thanks for the kind words 🙂 Where are you from in South Africa? Thanks a lot for spreading the word about MHOP, they are an incredible organization!!

Grew up in Joburg. Glad you introduced me to MHOP!

Cool. Look forward to following your blog + twitter 🙂

Wonderful stuff… that storm ran from South to North well over 800km and we are glad that you got the tweet!!!

Great writing – come and see us in Ghana!!

Thanks Cpt. Yaw! I will be seeing you in Ghana sometime soon!! A couple of months I hope!

Between the 35 hours of busriding and that massive storm I would have needed to get drunk I think?

hah, yeah.. Next time I’m in Ghana or civ I’m going to stock up on gin packets 🙂

Good point on the searching for money issue with the customs guys and the system being broken. I got stopped again the other night for not having my passport. My Malian Driving license is not sufficient ID for a Malian police man. I wouldn’t mind as much if I knew that the 2000 CFA I had to pay to enable me to continue on my merry path was going into the state coffers instead of his back pocket..

Your Malian driver’s license wasn’t enough?? So frustrating. Yep, would be a different story if the “fine” was actually going to the Malian government. Missing Mali right about now. Weather here has been stupid hot recently. Rainy season in Mali would be a big relief! How’s life at the camel?

You are a very patient person to be drenched, attacked by mosquitoes and stuck on a bus for 35 hours. One bonus, it seems like you get to know the people on the bus in those settings much more.

Normally, that is the biggest bonus of all, but I was definitely not as social as I normally am on this particular voyage.

Nice Post! I can relate to this oh to well atm.. I’ve been in West Africa since November last year and have had several horrendous trips.. Conakry to Freetown took 24 hours (its about 200km!) and recently in Niger the van I was in was also defeated by a large thunderstorm. I head to Bamako tomorrow, and then hope to get back to Mauritania by bus. I met some guys last year who said it took 48 hours… Let’s hope it’s not any longer!

Safe Travels, SaM.

48 hours to go to Bamako and Mauritania or 48 hours from Bko to mauritania? The latter seems reasonable. You are in for a long trip 🙂 Bonne chance. At least it’s not the hot season…

Enjoyed reading this, Phil! Everyone looked at me like I was crazy when I did a 14 hour bus ride in Mexico earlier this summer. I kept telling them that it could be much longer and much worse than 14 hours on a comfortable bus with aircon. This is a perfect example. I have yet to go to the Sahel, but experienced one of the craziest storms I’ve ever scene while packed into a car with family in Ghana. Driver kept on speeding along… tropical thunderstorm? No big deal 😛

Yeah most of the time they just power through the weather, as terrifying as it may be for us as passengers. I’ve seen some big storms in northern Ghana actually, which is more or less the Sahel at that point anyway.

sounds like a heck of a journey. glad you made it out alive, albeit a little soggy. i can’t help but wonder what “gin packets” are. i mean, obviously they contain gin, but…

you make making friends look easy. way to be a go with the flow kinda guy phil.

They are like slightly larger ketchup packets, except they have gin in them. And they cost about 30 cents 🙂 Thanks for your comment !

I am looking for a transporter to take 75 boxes weighing 2850 kg from Dakar to Bamako [Mali]

Hi Trevor, unfortunately I don’t have any specific recommendations I can offer. I would, however, say that you should definitely not take public transport with this quantity of things, because it will not work out well with the customs agents along the way. Sorry I don’t have a good alternative in mind.