Jakarta

Ja·kar·ta \jə-ˈkär-tə\The capital of Indonesia

a knockoff KTM 110 cc Chinese motorcycle

Matt and I had talked about this trip for a long time. After Matt successfully rode to Dakar from Bamako for his 40th birthday, he had ideas about a loop around West Africa, and to eventually sell the trip and variations of it to a certain kind of tourist. Those ideas remained just that until a few weeks ago.

UPDATE: we did in fact turn this trip into something. Head over to https://scootwestafrica.com/ if you want to join us for a scooter trip around West Africa.

This recon mission began in the Sleeping Camel workshop. Matt conceived a souped up jakarta that would allow us to carry tools, spare parts, food, extra water and fuel, kitchenware and our bedding. He is a skilled welder and metalworker, and it didn’t take him long to build a prototype with his own bike.

He cut 20 liter jerricans in half to make panniers.

He added a shelf on the front to hold a canister of fuel, and he installed a power point (a cigarette lighter socket) that he connected to the bike’s battery.

The finished product with the Guinean highlands as a backdrop (more on that later).

Jakartas can be found throughout West Africa, but the highest concentration of them is undoubtedly in Bamako. Contrary to their branding, jakartas are not made by KTM, an Austrian company best known for off road motorcycles. The jakarta “KTM” stands for KingTown Motors. Or sometimes KiangTown Motors, a good effort by the Chinese company churning out these bikes.

Why are they called jakartas? I have asked many people this question. I have heard two different answers. Some people have told me that the first person to import the bikes came from Jakarta. Others have told me that the bikes were at one time manufactured in Jakarta (or thought to have been manufactured there).

They are inexpensive bikes. In Bamako, a new jakarta is about $700, a considerable investment for many Bamakois, but still far more affordable than a used or new car. Parts and mechanics are both easy to find, and most repair jobs are only a few dollars.

Malians use these bikes to get around town. Some may use them to visit villages up to 100-150 kilometers away from Bamako. Everyone we spoke to before the trip thought we were insane to ride a jakarta for thousands of kilometers through multiple countries.

This much is true: the bikes are not fast. Our average speed hovered around 60 km/hr (about 40 mph), and even less than that on sand track. And speaking of sand, the jakartas handle sand about as well my 1984 SAAB handled ice in 2003 (the tires may not have been 20 years old but they sure felt like it).

Why travel 4,000 kilometers on these turtles? Well, if you were to ask me or Matt, the slow speed is actually the jakartas’ greatest asset. It forces you to focus on where you are instead of just racking up kilometers. Ride for 30 km and stop for a sandwich and a wander. After another 40 km, get a haircut at a roadside barber in a village. Further down the road, stop for a beer at a small maquis. Every time you hop off the bike, you have conversations. For me and Matt, this is the perfect trip.

We wanted to leave on Tuesday, February 7th, but we got into a real debacle at the Malian DMV. One day I will write about that. So we left for Dakar around 9AM the following morning.

We often joked that the most dangerous part of this trip was within Bamako city limits. The traffic may not be as manic as the biggest cities in West Africa, but the sheer number of jakartas keeps the entropy at full throttle. But we zipped out of town unscathed.

In a short while, we were in Kati, cruising past the empty cement trucks parked next to the customs post, getting ready for their return trip to Senegal. Then it was our first stretch of open road. With a tailwind, we blasted towards Kita.

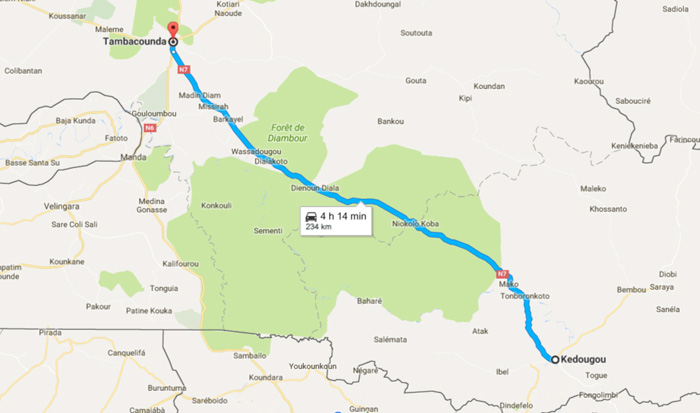

In Kita, we stopped at a service station to refuel and have a snack. We had a funny conversation with the cashier and a random Kita resident while scarfing down beef jerky and degué (sweetened yogurt with millet) in the air conditioned shop. It was during this conversation that we got the first indication of a bad road in Senegal between Kedougou and Tambacounda. But we’ll get to that later.

Some 40 kilometers after Kita, we turned onto a relatively new sealed road that would take us to Kenieba, a stones throw from the border of Senegal. The road was in excellent condition. Every now and then, a truck or a bus would tear past us, trying to break the sound barrier as they teetered around turns and double passed slower vehicles. But otherwise, this was a peaceful stretch of road that slowed down my thoughts.

We stopped in several villages to stretch our legs and refuel. Once the sun began its descent, we stocked up on water and headed into the bush.

We quickly mounted our mosquito nets and then Matt cooked a delicious meal of “mushroom” flavored ramen noodles. After dinner, I was out like a light. A steady breeze meant a good night’s sleep after a long day on the bikes. The following day would be even longer.

We woke up at sunrise and rode for 15 kilometers along the base of a plateau that changed from red to gold in the morning light. In Kenieba, we pulled into the parking lot of a service station. Women grilled brochettes and ambulant vendors vied for their first clients of the day. We grabbed a couple brochette sandwiches and washed them down with a concoction of nescafe and condensed milk. I used to drink these every morning at Madou’s kiosk when I lived in Abidjan. It is the cheap fuel that you can find everywhere, and it’s delicious.

Amadou was the barista doling out the hyper-sweet instant coffees. We eased into unguarded conversation, which is something you can do effortlessly with any Malian you come across. As we left, he gave us benedictions for the voyage ahead. I wished him well with his Arabic classes.

And then we were at the border. We checked out of Mali without issue. Crossing into Senegal would be the first test for the jakartas’ paperwork and my newly acquired Malian identification card. My Malian nationality was rejected almost immediately. The Senegalese police officer said that the Malian ID card is easily counterfeited. This was not an auspicious start to my ID card experiment. I probably could have fought him on it, but I had my American passport, and Americans don’t need visas for Senegal. Problem solved.

A young customs agent received us on the other side of the road. He had a good laugh when we told him that we were traveling to Dakar on jakartas. He then realized that he had never dealt with such a case.

Most jakartas aren’t formally matriculated. Drivers carry a vignette that they buy at the local mayor’s office. These cards confer ownership, but they aren’t made for crossing borders. Matt and I went through the unusual and tiring process of getting license plates for the jakartas, which would normally allow us to transit through Senegal for a certain number of days without issue. The customs agent told us he would need to consult with his chef.

While the chef was deciding whether or not to give us a “laissez passer,” we discussed road conditions with the younger customs agent. We had already heard about a cratered stretch of road that passed through the Niokolo Koba National Park. The customs agent doubled down on that and then repeatedly warned us about lions.

The chef eventually gave us the green light. Once we paid for our laissez passer’s, we were on our way. Getting from the border to Kedougou was straightforward. This road belied what was to come later on.

We arrived in Kedougou around noon. Uniformed schoolchildren walked and rode oversized bicycles alongside the neatly paved roads on their way home for lunch. We refueled in town, eliciting shrieks of laughter from the gas station clerk and other customers as we explained the jakarta trip. We then found a patch of shade in front of a mechanic’s workshop. We scooped up more degue (in Senegal it’s called thiakry, and for my money it’s even better than Malian degue. I think that’s because it’s a bit creamier) and a baguette. We made sandwiches of sardines, Vache qui Rit (a processed cheese that does not require refrigeration) and Sonia chili sauce. This sandwich was a revelation.

After lunch, we pressed on to the Niokolo Koba National Park. It looks easy enough on the map, but that green patch is a nightmare. The park is littered with tank traps and deviations of corrugated dirt track. I crept along like a senile geriatric and still nearly snapped off my foot brake on multiple occasions.

Several signs told us to be prudent, warning us of wild animals. There are indeed lions in this park. There are also hippos, elephants, rare giant Eland antelopes, and the northernmost population of wild chimpanzees in the world. We didn’t see any of these animals, but we did see a bushbuck leap across the road, a giant black scorpion that I thought was dead (it wasn’t), and a squirrel that Matt thought was dead (it wasn’t).

finally out of the park

My shoulders, thighs, knees and ass area were shot by the time we got out of the park. The jakarta was intact, though, and that was encouraging. By the time we rolled into Tambacounda, we were out of daylight and it was time to find a hotel.

A painting in the hotel bar

Matt led us to a hotel he was familiar with. It was clean and comfortable and they had cold beers at the bar. Dinner was a massive plate of chicken, frites and peas with a heap of chili sauce on the side. Everything was right with the world at this point. After a few more beers in the company of the entertaining bar staff, we retired to our air conditioned bungalow to get some sleep before the final leg to Dakar.

Tambacounda to Dakar is a hair over 450 kilometers. In normal circumstances, we would have done that in two days, taking our time in the villages and towns on the way. But we had two friends to meet in Dakar, and one of them only had a couple days there. So we gathered our things at first light and braced ourselves for another mammoth day. Dakar or bust. With stops, we had about 10 hours of riding in front of us in order to arrive in a city of 2+ million people around rush hour.

When we walked out to the bikes, Matt noticed that his jakarta had spent the night leaking gasoline. This was not a promising start to the day. Thankfully, Matt is a mechanic and he travels with spare parts. He quickly found and replaced the culprit, a cracked fuel filter.

Once we got moving, we were locked in. The road itself was impeccable. Quiet villages and massive baobabs punctuated the flat landscape. By the time we reached the salt flats leading into Mbour, arriving in Dakar before sunset seemed like a real possibility. The home stretch was not easy, though.

Matt proposed ditching the crowded two lane road between Mbour and Dakar for the highway, a toll road that sees much less traffic. The highway was considerably better in the sense that you didn’t have to worry about getting smashed by a truck every thirty seconds. In fact, the highway was empty, and it would have been a real joyride to Dakar if it wasn’t for gusts of wind that came from seemingly every direction. Battered by the wind for nearly 80 kilometers, the bright lights of Dakar provided the final shot of adrenaline we needed.

Tired but triumphant, we arrived in Dakar, dodging taxis and minibuses as we made our way to Ngor, on the edge of the Atlantic. It was time for a beer with friends. Little did we know, our trip was just beginning.

Want to join us for a trip? Sign up to our email list. Or visit https://scootwestafrica.com/.

Cool, Phil. Thanks for the story.